Why Does My Pelvic Pain Feel Worse When I’m Stressed?

Jan 19, 2026

Key Takeaway:

When you experience stress, your body’s fight-or-flight response causes the brain to unconsciously tighten pelvic floor muscles, often intensifying discomfort. Chronic pelvic pain is typically driven by an oversensitive nervous system acting like an alarm that triggers too easily, rather than a new physical injury. By leveraging neuroplasticity, you can retrain your brain to focus on safety instead of threat; utilizing breathing techniques and somatic tracking signals safety to the nervous system, effectively reducing flare-up intensity and restoring healthy pelvic function.

Introduction:

Do your pelvic symptoms get worse after a stressful week at work or a difficult family argument? You might notice more burning, pressure, or a sudden urge to urinate. This can make you worry that your condition is getting worse or that something new is happening.

Most of the time, the answer is no. Your pain is real. What’s happening is that when stress is high, your brain thinks you are in danger even when your tissues (muscles, nerves, organs) are safe.

Stress-related pelvic pain does not mean there is new damage to your tissues. It means your brain is responding to stress by sending protective signals, such as pain and burning, keeping your pelvic muscles on guard all the time. This learned overprotective response can be changed.

Central Sensitization: When your nervous system is on high alert

Many people reading this have already seen their doctors, had tests to rule out tissue problems, and tried treatments. Before we get into the science, remember this: persistent pain does not mean your body is broken or damaged. It means your brain is trying to protect you from things it sees as threats.

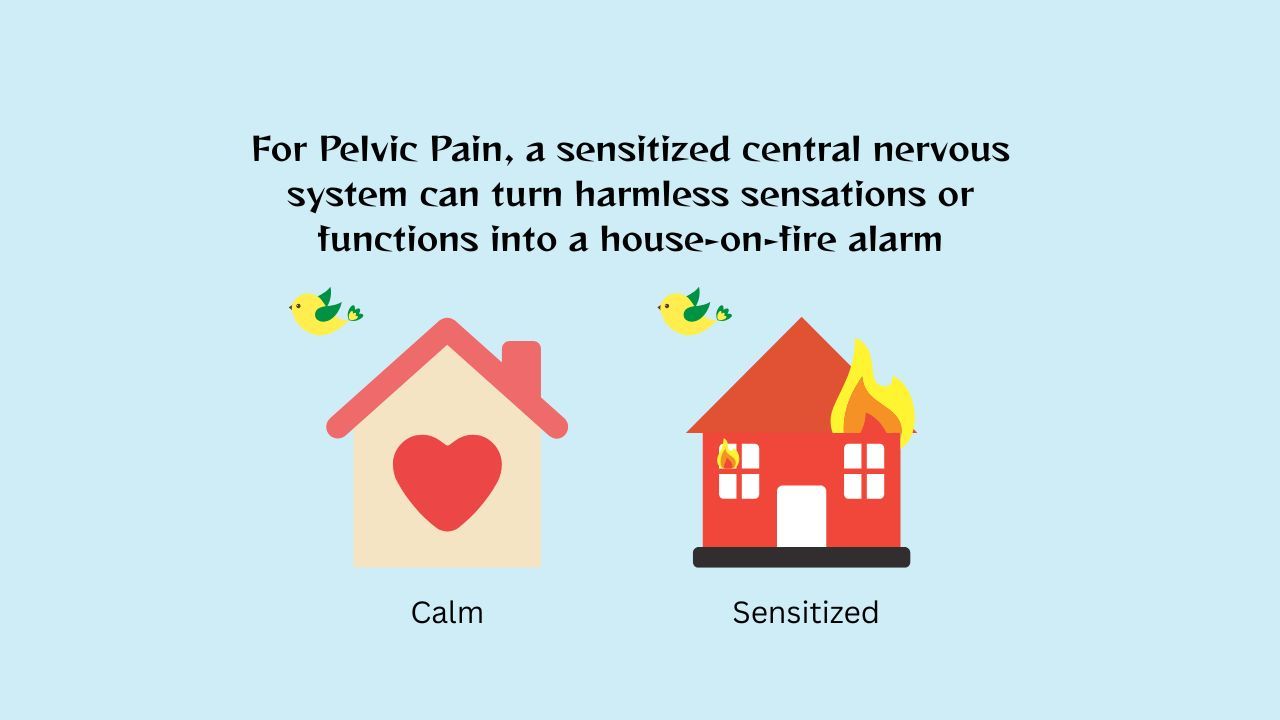

When we are healthy, our nervous system, immune system, and brain work like a home security system. If you get hurt, the alarm goes off to help you respond. With chronic pelvic pain, though, this system can become too sensitive. This is called central sensitization. (Nijs et al., 2011).

This process explains why many women experience a combination of lower back and pelvic pain; female anatomy and the nervous system are highly integrated, meaning an over-active alarm in the pelvis often sends protective signals to the muscles of the lower back as well. A process called wind-up makes the nervous and immune systems in your spine extra sensitive, so your brain tries too hard to protect you (Nijs et al., 2011).

Neuroplasticity: How the brain can change

People used to think the brain’s pain patterns never changed, but now we know that is not true. Neuroplasticity means the brain can form new connections and change how it responds to threats. This helps it send more feel-good chemicals and fewer pain signals.

If you have had pain for a long time, your brain has built a quick path for pain signals. With neuroplasticity, you can create new, safer pathways. Learning about pain and engaging in certain mind-body exercises can help weaken threat signals and strengthen safety signals (Louw et al., 2016).

How the Pelvic Floor Reacts To Stress

Long ago, people would curl up to protect their stomachs and organs when they were in danger. This reflex uses the pelvic floor muscles. Even though we do not face wild animals today, our bodies still react to stress, like a tough email or a deadline, in the same way.

When your pelvic floor muscles stay tense from stress, they get tired and do not get enough oxygen. This often results in a persistent lower back pain pelvic ache that can feel like a heavy or dull pressure spreading through your midsection.

Here is how the cycle often works:

- Stress signals danger

- The brain tightens the pelvic muscles

- Tension reduces oxygen and creates discomfort

- The brain notices the discomfort and further increases protection

- Pain increases even without injury

This helps explain why stress can cause real physical pain even when there is no new tissue damage.

A Roadmap to Recovery: Sarah’s Story

Sarah is a 34-year-old who lives with endometriosis and pelvic floor tension. For years, she noticed a pattern: whenever work got stressful or family conflict arose, her pelvic pain would spike. The burning sensation and pressure would become unbearable. She started avoiding plans, expecting the pain to show up.

When Sarah started PelvicSense her first change was understanding what was really happening. She learned that her constant stress wasn’t just making her feel bad emotionally. It was teaching her brain to stay on high alert. Every deadline became a trigger, not because something was wrong with her pelvis, but because her brain had learned to expect danger.

Sarah decided to stop waiting for the pain to start before taking action. On days when she felt less discomfort, she practiced breathing and listened to calming audio. She started thinking of it like brushing her teeth, something she did every day whether or not there was a problem. Slowly, her body started to feel safer.

Six weeks in, Sarah faced a major work deadline. In the past, this would have meant two weeks of severe pain. This time was different. She felt the warning signs: the tightness starting and the familiar dread. Instead of spiraling, she used what she had been practicing. She re-read an educational module and listened to one of the audios.

The flare came, but it didn’t last. It stayed for a few hours, maybe a day, and then it passed. Sarah couldn’t believe it. For the first time in years, she didn’t feel helpless. She had tools that actually worked.

She wasn’t just surviving her pain anymore. She was changing it. Sarah did not heal by pushing through pain. She improved because she stopped treating her body like a problem and started sending steady safety signals to her brain.

How to show your brain that you’re safe

To break this cycle, you need to calm your body’s automatic responses, not just your thoughts. A structured approach can help. PelvicSense gives you a clear plan with pain science education, calming exercises, and gentle breathing and movement to quiet your body’s alarm system (Hecht, 2025).

If you are not sure where to start, begin with breathing. It is the fastest way to calm your nervous system. Once breathing feels comfortable, add somatic tracking. Movement comes later.

- Paced diaphragmatic breathing does more than help you relax. When you breathe in, it gently lowers the pelvic floor from the inside. As you breathe out, the pelvic floor moves up to its normal resting position (Park & Han, 2015). Try breathing in through your nose for four seconds, then out through pursed lips for six seconds. Repeat this five times and see if you feel a bit calmer.

- Somatic tracking works best when you are not in a flare. Sit or lie down in a comfortable position and quietly describe what you feel without using scary words. For example, if you are experiencing what feels like a sudden stabbing pain in pelvic area, female physiology often responds by bracing or guarding. If you are noticing persistent pelvic and left side pain, Instead of saying It's stabbing me, you could say I feel a warm, buzzing sensation in my left sit-bone. This helps your brain process the feeling in a new way. (Ashar et al., 2022).

- Graded exposure to movement means starting with movements that feel safe, like a pelvic tilt while lying on your back or slowly rocking your thighs to each side as you breathe. These gentle shifts are designed to soothe back pelvic pain by teaching your nervous system that movement is not a threat. As your brain learns these are safe, it will start to relax the guarding reflex (George et al., 2010). PelvicSense offers over 45 different body movements you can practice over time.

Common Questions About Stress and Pelvic Pain

If my pain is triggered by stress, does that mean it is all in my head?

Absolutely not. The pain you feel is completely real. When we talk about the brain’s role in pelvic pain, we mean biology, not imagination. Your brain is the organ that processes every sensation in your body. In chronic pain, the brain’s processing software becomes over-reactive. The pain is felt in your tissues, but the volume is being controlled by a sensitized nervous system.

How long does it take for neuroplasticity to work?

Neuroplasticity is not an overnight fix; it is a gradual process. Most people begin to feel a shift in their internal alarm within three to four months of consistent practice. By ninety days, which is the length of the PelvicSense roadmap, the brain has usually created enough new, safe neural pathways to significantly lower the baseline of daily pain (Hecht, 2025).

Should I wait for a flare to start my PelvicSense exercises?

The best time to use PelvicSense is not during a flare. Think of it like training for a marathon. You build your strength during the quiet times. Practicing calming mind and body exercises consistently over time helps prevent long, frequent flares from happening in the first place.

If you are currently in a flare, choose the easiest skills you find helpful, such as the ones you have already practiced and feel comfortable with. This is the time to re-read your ebook listen to a Learn module, or play one of the calming Rewire audios to soothe the upregulation pattern. Remember, flares are short-lived.

Why is the pelvic floor so sensitive to emotional stress compared to other muscles?

The pelvic floor is embryologically and neurologically linked to the limbic system, the emotional center of the brain. Because the pelvis houses our reproductive and excretory organs, the brain considers this area a high-priority target for protection.

Summing up

It is important to know that ongoing pelvic pain or distressing sensations do not mean your body is broken. Instead, it shows your nervous system, immune system, and brain are working too hard to protect you. The guarding reflex helped us survive in the past and is useful for a short time, but with chronic pain it is like an alarm that will not turn off.

You do not have to feel powerless over your next flare. By learning about central sensitization and how neuroplasticity can help, you can start moving your body from a state of high alert to one of calm and connection.

PelvicSense gives you a step-by-step plan with pain science education, calming exercises, and gentle breathing and movement to quiet your body’s alarm system. This self-paced approach helps you take control of your recovery and teaches your brain it is safe to relax. Healing is not about fighting pain. It is about showing your nervous system, immune system, and brain that you are safe.

References

- Nijs, J., et al. (2011). "Central sensitization in chronic pain conditions: Mechanisms and assessment." Manual Therapy. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21632273/

- Louw, A., et al. (2016). "The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature." Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27351903/

- Hecht, E. (2025). "Digital Health Intervention for Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Pilot Study on PelvicSense." Abstract link: https://tinyurl.com/yeca523x.

- Hannibal, K. E., & Bishop, M. D. (2014). "Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: A psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation." Physical Therapy, 94(12), 1816-1825. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25035267/

- Park, H., & Han, D. (2015). "The effect of the correlation between the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles and diaphragmatic motion during breathing." Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(7), 2113-2115. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26311933/

- Ashar, Y. K., et al. (2022). "Effect of Pain Reprocessing Therapy vs Placebo and Usual Care for Patients With Chronic Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial." JAMA Psychiatry, 79(1), 13-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34586357/

- George, S. Z., et al. (2010). "Comparison of graded exercise and graded exposure clinical outcomes for patients with chronic low back pain." Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(11), 694-704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20972340/